“We make mountain wines here,” says Sebastián Zuccardi, stating the obvious. He’s standing in front of the solid-stone winery he built two years ago in Uco Valley’s Altamira district at nearly 4,000 feet above sea level where his estate vineyards practically hug the snow-capped Andes Mountains.

Since joining his family’s Maipu-based wine business, founded by his grandfather in the 1960s, Zuccardi has been convinced that Uco Valley is the future for Argentina, and he has devoted most of his energy and resources to getting as close to the mountains as possible.

“The combination of calcium carbonate-rich, alluvial soils at this elevation is unique to Uco Valley,” he explains. “We can make fresh, mineral-driven, high-energy wines here—totally different from the fruity, formulaic Malbecs that people associate with Mendoza. Uco is barely two decades old, so we are just now beginning to understand our terroir.”

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

Zuccardi is among a growing group of passionate producers working to classify Uco’s high-elevation terroirs and petition for Geographical Indication (GI) status for the emerging districts that, although young, are responsible for Argentina’s paradigm-shifting wines.

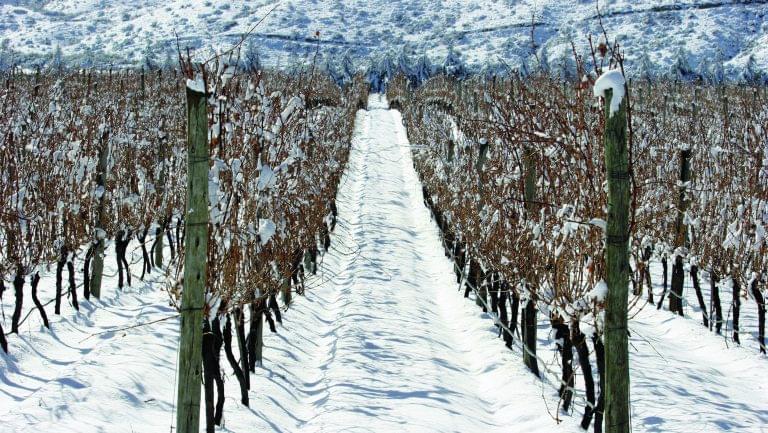

Too High, Too Cold, Too Harsh

When Nicolás Catena planted his Adrianna Vineyard in Uco’s Gualtallary district in 1993, most believed he would fail. Lower Uco had some vineyards, but no one had dared cultivate grapes at 5,000 feet above sea level; the risk of frost was extreme, and growers assumed grapes couldn’t ripen in the harsh, high-desert landscape.

But Catena was determined to find the coldest place in Mendoza to plant vines, and the introduction of drip irrigation to the region meant that viticulture at higher sites was finally possible. He set up weather stations throughout the region and discovered that while temperatures were similar to Champagne, the brightness and extra hours of the sunlight could result in the holy grail of winemaking: “Grapes on the edge of ripeness with fully mature tannins, natural acidity, and only 13 percent alcohol,” explains his daughter Laura Catena, who now manages the family’s Bodega Catena Zapata.

Around the same time, Dutch entrepreneur Mijndert Pon saw similar potential in Uco’s higher reaches. But instead of a single vineyard, he bet much bigger, planting hundreds of acres of mostly Malbec vines between 1996 and 1999, and constructing a massive, gravity-fed winery christened Bodegas Salentein. The first to put “Uco Valley” on its labels, Salentein is locally regarded as the region’s “locomotive.”

The results from these pioneering vineyards were evident within several harvests. Grapes grown here possessed higher minerality, more acidity, and firmer tannins compared to lower sites. “I had never seen acid levels like this in Argentina before,” describes Salentein’s winemaker of 20 years, José “Pepe” Galante (formerly the winemaker at Catena). “They are the same as Chablis.”

Word spread quickly. The last two decades have seen explosive growth in Uco with dozens of new wineries and high demand for Uco fruit from producers outside the region. Vineyard prices have increased twenty times in some coveted districts. Trailblazers have continued to test limits, planting successful vineyards well over 5,000 feet and others are pushing higher still: José Lovaglio, owner and winemaker of Vaglio, and the son of Susana Balbo, has planted a Pinot Noir vineyard (not yet in production) in Uco’s La Carrera district that sits above 6,500 feet.

An Appellation Renaissance

As many of these original vineyards come of age, the terroir conversation has shifted from simply elevation to include soils, a topic Uco winemakers are obsessive about. Some vineyards have dozens of calicatas—eerily grave-like pits dug in between vines to expose various layers of subsoil. Some reveal large round boulders, others marine fossils, pebbles, or chalky calcium carbonate deposits; various combinations of material left behind when glaciers and rivers pushed alluvial deposits down the slopes of the Andes millions of years ago.

Zuccardi dug 180 calicatas in his Piedra Infinita vineyard alone (source of the acclaimed single vineyard Piedra Infinita Malbec), which uncovered 40 different soil types. Laura Catena identified more than 200 distinct parcels in the Adrianna vineyard, which she now vinifies separately. For producers here, the tremendous diversity of soils and microclimates is what makes Uco so distinct from Mendoza’s two other growing areas—Maipu and Lujan de Cuyo—and what they believe calls for a more specific classification system.

“Our growers have been pushing hard for this GI system in Uco to focus on regional specificity,” says Jonathan Chaplin, co-founder of Brazos Wine, a Brooklyn-based import company which represents many of the new small-scale Uco producers. “No one in Argentina was talking about regions ten years ago, and today that’s all we do—we bring maps everywhere.”

This new laser focus on terroir coincides with a move towards a fresher wine style in Uco—and not only from the younger generation of producers. “Today we make wines that are focused on the place, with less new oak and earlier harvest dates,” says Zuccardi, who installed 160 concrete eggs and large foudre at his new winery. “Working with concrete and large vats is a return to the winemaking culture of the 1930s.” Salentein and other established names like Matías Riccitelli and Paul Hobbs report picking their fruit as much as a month earlier than in the past and using more whole-cluster fermentation for added freshness. With less alcohol and extraction, a clearer picture of Uco’s regional diversity is coming into focus.

Gualtallary: A Sunnier, Drier Burgundy

In a corner of Uco’s Tupungato region with vineyards climbing to a mile above sea level, Gualtallary stands out for its rocky, alluvial, chalky soils. Convinced this high mountain oasis was ideal for organic farming, Languedoc vigneron Jean Bousquet planted vineyards in the shadow of the Tupungato mountain in the early 1990s. Today, Domaine Bousquet is the largest exporter of organic wine from Argentina, producing 300,000 cases of (shockingly affordable) wine. Bousquet just debuted their first unoaked, sulfite-free wine, Virgen Malbec.

“Gualtallary is freshness and elegance,” says daughter Anne Bousquet, who now runs the domaine. “We get bright red berry, mineral, and floral notes in our wines, as well as more structure.” Indeed, The Catena Institute research center found that the unique luminosity of mountain sunlight in Gualtallary increases tannins in grape skins.

Gualtallary producers find intense terroir expression coming from even very young vines. Edgardo (Edy) del Popolo and David Bonomi left jobs at commercial wineries to plant bush vines that naturally yield 40 percent less fruit than the region’s average—under one pound per plant. Their first vintage, 2012, showed an aromatic complexity and fine-grained tannins that would take years to develop in young vines grown in other regions, Popolo believes. “In Gualtallary we are able to craft wines with rare purity that really speak of their landscape.” (Gualtallary has yet to be officially approved as a GI because the name is a registered trademark owned by a single producer.)

Cabernet Franc is generating a lot of interest here today; though less than 1 percent of plantings, it’s the district’s most exciting grape, many claim. “Gualtallary is the best place for Cabernet Franc in Argentina—it needs elevation,” says Matias Michelini, who founded Zorzal with brothers Gerardo and Juan Pablo in 2007. Fermented and aged in concrete eggs, Zorzal’s Eggo Franco is peppery, savory, and earthy with electric acidity. Domaine Bousquet, Rutini, and Andeluna are also big Cabernet Franc champions here.

Paraje Altamira: Structured, Savory Malbec

In the southern Uco Valley, the Paraje Altamira district broke away from the larger La Consulta region in San Carlos in 2013—the first GI declared based on terroir research, not political boundaries, which paved the way for Uco’s GI system’s evolution. Achaval Ferrer’s Finca Altamira is arguably the district’s most famous wine; more recently Zuccardi and Altos Las Hormigas have built wineries here.

Altamira features heavier soils than Gualtallary, with loads of silt and calcium carbonate—and some very large rocks (which makes planting vineyards costly and difficult). Wines here tend to be fuller-bodied with dark fruit and herbs; Malbec—by far the district’s star grape—shows power and concentration with fresh acidity. Zuccardi’s Poligonos Altamira, one in a series of single vineyard Malbecs made in different districts, illustrates Altamira’s unique underlying salinity. “The calcareous soils here force vines deeper and add structure, which the Malbec variety can often lack,” Zuccardi explains.

San Pablo: Uco’s Coolest, Wettest District

San Pablo is Uco’s newest GI, approved in 2019 following a three-year research effort led by Zuccardi, Patricia Ortiz’s Tapiz estate, and Salentein. A newer area with a remarkably distinct microclimate, San Pablo sees more rain and humidity than other districts—and often snow. “San Pablo makes wines with tension,” says Galante. “It’s not common to see this relationship between low pH and alcohol, which gives aromatic intensity and freshness.”

Salentein’s Nogales vineyard, at the southern end of San Pablo, gets enough rain to make dry farming possible—an extreme rarity in Mendoza (which has the lowest rainfall of any wine region in the world). Its Las Sequoias vineyard—the highest in San Pablo, planted to Chardonnay and Pinot Noir—is lush and green, surrounded by 80-year-old redwood trees, a bizarre sight in the middle of the desert. “It’s a microclimate within a microclimate,” Galante describes.

Zuccardi picks his nine-year-old San Pablo vineyard—source of his salty Fósil Chardonnay and peppery Poligonos Cabernet Franc and Malbec—almost a month behind his other sites, and the grapes still result in wines with lower alcohol levels, he reports. Wines here also possess an unusual color intensity, observes Tapiz’s Patricia Ortiz (the reason she named her single vineyard San Pablo Malbec “Black Tears”).

Chacayes: Hotbed of Experimentation

Granted GI status in 2018, Chacayes has long been an innovative area. Francois Lurton pioneered the region in 1996 when he came “looking for freshness,” reports Piedra Negra’s winemaker Thibault Lepoutre. The region’s rocky, non-fertile soils are extremely difficult to plant, he explains; those undeterred are rewarded with wines high in natural acidity, tannin and color—and the ability to farm organically without too much effort.

The trend here has moved towards natural, non-interventionist winemaking. Lepoutre has transformed Piedra Negra’s icon bottling, L’Esprit de Chacayes, by picking one month earlier, fermenting in concrete eggs, and moving away from new oak. He’s also now making a sulfite-free Malbec, a project that took him five years to perfect.

At their SuperUco winery, the Michelini brothers (of Zorzal and Passionate Wines), have been working biodynamically since 2012, and plant vines in non-traditional concentric circles based on ripening cycles; they ferment with native yeasts in egg-shaped clay amphora. “Because of the very low pH we have at harvest, it’s so much easier to make natural wine here; bacteria is less of a problem,” says Matias Michelini.

Chacayes terroir suits a wide range of varieties beyond Malbec. Piedra Negra produces a large amount of Pinot Gris, and their impressively ageworthy Gran Lurton White is based on Friulano and Viognier. Luis Reginato, another leading force in Chacayes (and director of viticulture for Catena Zapata), is making a skin contact, concrete-fermented Gewürztraminer under his Chaman label.

Eduardo Soler founded Ver Sacrum in Chacayes in 2012 to focus on Rhône grapes with cuttings from an old Maipu planting. “For years, color and quality were perceived as the same thing, so Grenache disappeared from Argentina—we want to bring it back.” His bush-vine Garnacha and Monastrell (Mourvedre) are both marked by floral, white pepper, cool-climate character; the Ver Sacrum Geisha de Jade, a Marsanne-Roussanne blend aged 12 months on lees under a veil of flor, is honeyed, nutty yet bright. “My aim is to challenge the image of Argentina as a producer of only overripe, high alcohol wine,” says Soler.

As experimentation continues in Uco, new GIs are carved out, and maturing vines become increasingly expressive of place, a new perception of Argentina has already begun to supplant the old.

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Kristen Bieler is the former editor in chief of SevenFifty Daily and the Beverage Media Group publications. Based in New York City, she has been writing about wine, spirits and food for nearly two decades, and her work has appeared in GQ, TASTE, and Food & Wine Magazine’s Annual Wine Guide, among others. She is also a judge at the Ultimate Wine Challenge. Follow her on Instagram: @bielerkristen.