We live in an age of transparency. Today’s consumers—especially the millions of younger millennials who grew up with the ability to instantly Google for the answer to any question—expect to know a lot more about the food and beverages they buy than their parents or grandparents ever did.

And yet ironically, one of mankind’s oldest beverages, wine, has remained stubbornly immune to this trend. Look at your typical wine bottle today, and aside from a warning that it Contains Sulfites, and maybe some colorful prose about the winemaking technique, or the grapes used, there’s usually no mention of the ingredients. Yet many winemakers routinely use a wide range of additives or processing materials that the average consumer might be surprised to learn about.

For example, how many wine drinkers are aware that the color of their wine may have been intensified by an additive called Mega Purple to give it a darker, richer appearance? How many vegetarian or vegan imbibers are aware that egg whites, or an ingredient made from fish bladders called isinglass, may have been used as a fining agent to clarify their wine? The list goes on, with a wide variety of other common additives expanding the options modern-day winemakers have at their disposal for tweaking their production.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

This lack of transparency clashes with what today’s consumer has come to expect. According to a recent report by the marketing research consultancy FutureCast, “Consumers ask, how is the food I’m buying enhancing the quality of life for my family or myself? How does it reduce negative impacts on my well-being?”

The Matter of Labeling and What to List

Perhaps it’s not surprising that a growing call is being heard among some in the wine industry to expand the amount of information required on labels. But they are so far a small—though often vocal—minority.

The San Francisco–based Wine Institute, which represents more than 1,000 wineries and affiliated businesses in California, says the issue is not a priority for the industry—or for that matter, wine consumers. Says Nancy Light, the organization’s vice president of communications, “We do not believe there is interest within the California wine community in additional mandatory labeling requirements and know of no significant push by wine consumers for this information.”

Yet some winemakers view the matter as an important one and have voluntarily listed more ingredients on their own labels even though they aren’t required to do so.

For example, Ridge Vineyards, based in Cupertino, California, has been listing ingredients on its wine labels for some time as part of what it calls its preindustrial approach to winemaking. “We believe that for anyone attempting to make fine wine,” explains the company on its website, “modern additives and invasive processing limit true quality and do not allow the distinctive character of a fine vineyard to determine the character of the wine.”

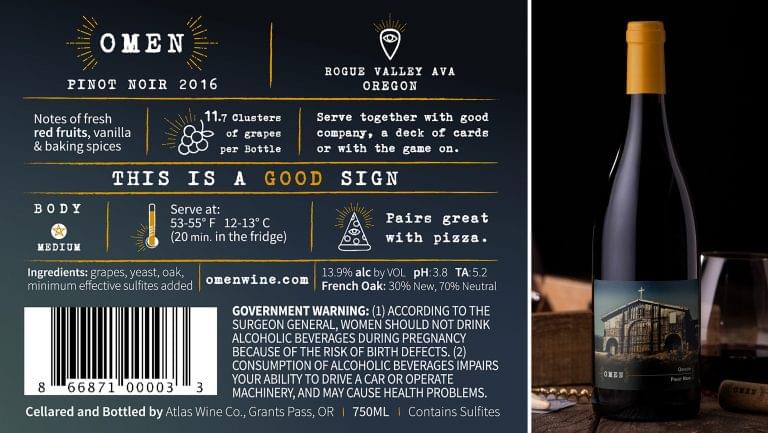

Another winemaker, Alexandre Remy, a partner in the three-year-old Atlas Wines in Napa, California, began including an expanded list of ingredients on his wines this year. “When I started my Atlas Wines Company,” he says, “the biggest thing [I was trying to work out] was, how do I differentiate myself? And I know that most big companies use a lot of additives, like gum arabic, like sweeteners, artificial color, artificial oak, artificial aromatics. You name it. Is it dangerous for you? It’s not dangerous. But I think the customer should know that their wine has been tweaked a little bit.” For Remy, the expanded ingredients list is a way to highlight the fact that Atlas does not use additives like gum arabic, Mega Purple, or any other artificial enhancers.

Marnie Old, a sommelier and the author of Wine: A Tasting Course, wonders whether it would really be useful to consumers if the U.S. Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) were to expand its labeling requirements beyond sulfites.

“I think you would have a situation where the ingredients list would read something like grapes, yeast, and oak, because the one thing we routinely use in wine that does leave a detectable presence is oak barrels,” she says, pointing out that additives like fining agents generally aren’t “detectably present” in the final wine. With regard to Mega Purple, she says that because it’s made from concentrated grapes, it shouldn’t necessarily be considered an ingredient distinct from the wine’s primary ingredient. She concedes, however, that Mega Purple could be listed as something like “grape skin extract” to differentiate it as an additive. But if winemakers were only required to list ingredients like grapes, yeast, and oak, she concludes, “it seems to me that the argument for ingredients labeling is significantly weakened.”

Even so, Mark Kuspira, founder and proprietor of Crush Imports, based in Alberta, Canada, believes expanded wine ingredients labeling is on trend with what’s happening throughout the food and beverage industry. “I think it’s going to be a huge trend,” he says, “and I guarantee, probably within 10 years, it’s going to be mandatory to list what’s in your wine on the back label. People just really want to know what goes into their bodies.”

For now, though, the wine industry at large doesn’t appear to be in any rush to address such labeling concerns. George Feaver, the wine director of PJ Wine, a retail shop in Manhattan, points out that having to list more ingredients on a wine bottle would disrupt an industry that has operated on a certain public perception for centuries. He says, “It would take away from the illusion that people are getting wine in the cultural context that they think wine is coming from—coming from nature.”

But that doesn’t necessarily mean the drive for transparency won’t win out in the end. “I think it’s fair to say that this [interest in transparency] is growing because we simply have more information than we used to have, and it’s easily shared,” says Old. “We demand more information now than we used to from winemakers about precisely how they make their wines. Those kinds of questions are in part just coming from this changing landscape of information that we inhabit. And a certain part of it also comes from the [transparency involved in the] local food, farm-to-table, and nose-to-tail [movement] that we see on the food side. People are asking similar questions now about their wines that they’ve learned to ask about their vegetables and meat and so on.”

But Old also points out that any ingredient labeling changes would be a complicated affair given the global nature of the wine industry. “If it happens,” she says, “I think it will be because one major player desperately wants to do it and forces everyone else. For example, I would say it’s probably more likely that the E.U. would force ingredient labeling than the U.S. would.”

Transparency as a Marketing Strategy

As the dialogue evolves, smaller winemakers, like Atlas’s Remy, are already moving ahead with the notion that transparency can give them a strategic advantage over their bigger rivals. “The most successful businesses today are about transparency,” says Remy. “And the customer is under the impression that wine is a natural product. So my fight is to differentiate myself by being as transparent as I can be.”

He expects it will take a while for full transparency on wine labels to catch on, but he’s committed to providing products that are popular with consumers—and that are fully transparent. He doesn’t necessarily think that transparency itself is what attracts consumers to his wine the first time, but he believes it’s part of what keeps them coming back. “I always believed that the wine industry needed to educate its consumers better,” he says, “and I think that by providing transparency, you start to create trust, and by having trust, you create [successful] brands. That’s basically my business strategy.”

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Andrew Kaplan is a freelance writer based in New York City. He was managing editor of Beverage World magazine for 14 years and has worked for a variety of other food and beverage-related publications, and also newspapers. Follow him on Twitter at @andrewkap.