At a moment when sommeliers are landing feature-length film documentaries and glossy magazine photo shoots, and being hailed as “rock stars,” a number are finding that their ambitions lie beyond working the floor. Some are choosing to get their hands dirty by turning at least some of their attention to making wine too.

A number of the biggest names in restaurants, including Rajat Parr (formerly of Michael Mina restaurant group), Bobby Stuckey (Frasca), and Jordan Salcito (Momofuku), have launched their own successful labels (Sandhi, Scarpetta, and Bellus, respectively), and a new crop of somms are following suit.

The appeal for the consumer is obvious: Having a trusted sommelier at the head of a brand is nearly the same as getting a wine recommendation from a sommelier. But what is it that’s propelling the sommeliers away from the restaurant floor? For some, the transition offers a look at another side of the wine industry—the process of making the wine rather than selling or drinking it. Others jump at the opportunity to dig further into favorite regions and grapes. For working sommeliers, winemaking offers an additional income stream from nonrestaurant hours.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

The projects somms engage in run the gamut, from owning the brand to hands-on work, including actually harvesting grapes, hauling hoses around the winery, deciding on the final blend—and, returning to their sommelier roots, selling the wine. Many choose to work with established winemaking teams rather than wing it in the winery.

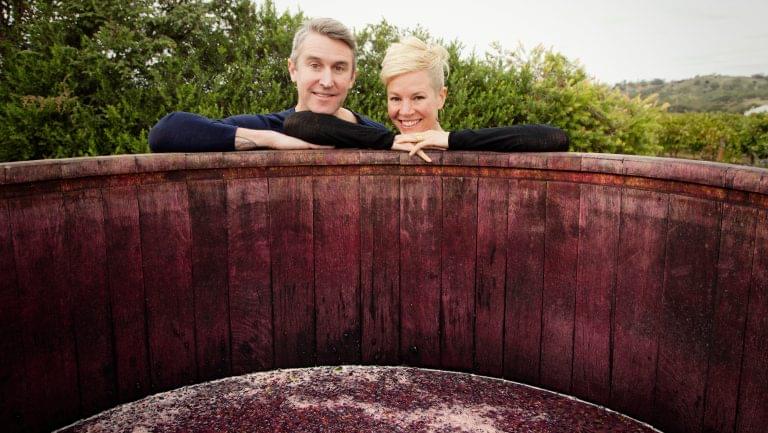

What’s inspiring the majority of these somms to actually make wine is the chance to exercise the expertise gained from tasting, just in a different format. “It was very helpful having the opportunity to taste a large variety of winemaking styles as well as different regions and varietals,” says Carla Rza Betts, who worked as a sommelier at New York’s John Dory Oyster Bar and the Spotted Pig. Rza Betts and her husband, Richard, a master sommelier turned book author, now make wine—doing everything from harvesting to creating blends—under the label An Approach to Relaxation. (Richard has worked with other brands as well, including My Essential Wine, Betts & Scholl, and Saint Glinglin.)

Rza Betts says their sommelier experience has come in particularly handy as they developed their new Sémillon, Nichon. “We both loved Sémillon as somms but had never made it,” she says. “We didn’t really know what to expect. We assumed it would take twice as long in bottle to get where it is now; all our other favorite Sémillons from around the world need much more time, and yet while tasting Nichon over the past year, we were very surprised—and excited—to see that it’s opening up much faster than we expected.”

That global perspective that comes from tasting wine around the world can give insight into how regions compare, says former sommelier Joe Campanale.

Campanale agrees that sommeliers’ tasting experience is helpful when it comes to making wine. “I was trying to find where there was more to be added to the conversation,” he says, discussing how he came to make wine in Abruzzo, Italy, under the Annona label. Campanale, who built a mini-empire of restaurants in New York with a focus on Italian wine, including dell’anima, L’Artusi, and Anfora, noted that in his time tasting a substantial quantity of Italian wine, he had found only two wineries that intrigued him in the Abruzzo region, Emidio Pepe and Valentini, but not much else. And in that void, he saw an opportunity.

Campanale used his globally informed vantage point to create something new in the region in conjunction with Third Leaf Wines, a company that partners with industry leaders to create new wine brands. (Other projects from the company include Gothic, a line of Oregon Pinot Noir made with the sommelier Josh Nadal and the restaurateur William Tigertt.)

Obviously, having a good palate doesn’t directly translate into knowing how to make wine, but in some ways it opens up possibilities in the process that trained winemakers might not think of. “Some [of my ideas] weren’t practical,” Campanale says, noting that he travels to Abruzzo three or four times a year and is in constant contact with his winemaking team, which includes Stefano Papetti Ceroni of De Fermo wines. But some of his ideas turned out well—for example, a short skin fermentation in concrete tanks with Montepulciano grapes for his Modo Antico. “We can get a lot of flavor without it being overly tannic, [and make] a flavorful, juicy, structured wine,” he says, likening it to a cru Beaujolais.

That sort of intuitive reasoning that comes from exposure to great wines is an invaluable resource, says somm-turned-winemaker Larry Stone. Stone, a master sommelier best known for his work at Chicago’s Charlie Trotter’s and San Francisco’s Rubicon, may be one of the original sommelier-winemakers. In 1983 he started his own négociant line, and since then he’s consulted on winemaking for Francis Ford Coppola and Daniel Johnnes. His latest project, Lingua Franca, is a partnership in Oregon with David Honig, and Burgundian superstar winemaker Dominique Lafon as a consultant.

Stone says one of the biggest surprises in building Lingua Franca was uncovering his own latent talent in identifying good vineyard sites, a talent he suspects comes from visiting the best vineyards in the world. “I didn’t study geology as a subject,” he says, “but [as a sommelier] I developed an intuitive understanding of soil and microclimates that enabled me to source good vineyards.” And when it came to sourcing and planting his new vineyard in Oregon’s Eola-Amity Hills, Stone says he was never uncertain about the site and his plans. “Experts came by and validated what I was doing,” he says. “Pedro Parra [one of the foremost winemaking consultants in the world] thought our site was the best in Oregon.”

Stone, who also plans to sell grapes to Penner Ash and Cristom, has high hopes for his project: “It’s going to be fun for the next 20 years.”

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.